Open problems solved by AI

What are the current math capabilities of AI? A huge question; I want to contribute with the following experiment. I will take a clearly defined open problem in mathematics

It can; kind of. I tried this for about 50 problems with GPT-5 and obtained a few results I consider nontrivial. I will share two examples in combinatorics; aside from the problem statement, the following solutions are 100% AI, including writeup.

It should be said that the following two questions can barely be called “open problems”. The questions are not well-known and not even conjectured in a peer-reviewed article. I learned of one problem from a somewhat obscure booklet of open problems and the other from a research pitch by a fellow mathematician. Yet these are questions that someone working in the relevant area wondered about and did not immediately have a solution for.

Context

I’m not aware of others showcasing examples of this kind. There are benchmarks like FrontierMath and Humanity’s last exam. These are extremely useful, but different in that the problems under question have a known solution, so it’s a bit harder to gauge what, e.g., “50% of problems solved” means.

Many mathematicians also use AI in their work, but it is typically hard to disentangle what part of the work is done by human and what part by the AI.

Tightness of a recent paper on 2D tiling

There was a cool recent paper about tiling the plane $\mathbb{R}^2$ with polygonal tiles. One of the results in that paper is that every tiling of the plane with rational polygonal tiles is weakly periodic: it can be partitioned into finitely many pieces, each of them singly-periodic.

Can this theorem be improved? Can we prove that every polygonal tiling is simply periodic? It turns out that the answer is no. AI can find a specific example of a polygonal tiling that is weakly periodic but not periodic.

Here’s the example (fully AI written).

A counterexample to a problem about functions

Here’s a fact about functions that has applications in graph theory.

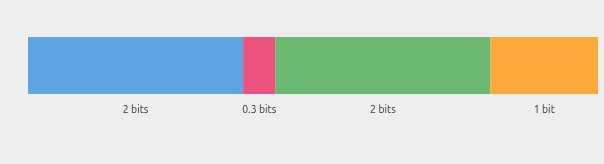

Consider two functions $f$ and $g$ from a set $E$ into a set $F$ such that $f(x) \neq g(x)$ for every $x \in E$. Suppose that there exists a positive integer $n$ such that for any element $z \in F$, either $\lvert f^{-1}(z) \rvert \le n$ or $\lvert g^{-1}(z) \rvert \le n$. Then $E$ can be partitioned into $2n + 1$ subsets $E_1, E_2, \dots, E_{2n+1}$ such that $f(E_i) \cap g(E_i) = \emptyset$ for each $1 \le i \le 2n + 1$.

Can we generalize this theorem to more functions? It is unclear how many sets would be needed in the partition if we generalize from $2$ functions to $k$ functions.

A particularly bold question was asked at KAMAK, the yearly retreat of combinatorics researchers from Charles University (first problem in this booklet). Maybe $2n+1$ sets is still enough?

This turns out to be too optimistic. Given this problem, AI came up with a straightforward construction showing that if you generalize the problem to $k$ functions, you need to partition into at least $kn$ subsets.

Here’s the short proof (fully AI-written).

Beginnings

Neither of the solved problems is that interesting; if I solved a problem like this, I would not bother publishing, I would just write to the authors of the original paper and hope that something more interesting comes out of it.

But look: beginnings always look like this. Take the first program that beat a chess grandmaster. A legitimate reaction to this event was that the grandmaster was “badly off form.” Yet, Kasparov has been beaten less than 10 years later. Similarly, I expect that in the coming months we will see examples that look more and more legitimate and be surpassed within 10 years (and maybe much sooner).