Practical k-means algorithms

In the \(k\)-means problem, we are given a set of points \(X\) (in Euclidean space) and a parameter \(k\). The task is to find \(k\) points, called centers, \(C\) to minimize the cost

\[\sum_{x \in X} \text{min}_{c \in C} \lVert x-c\rVert^2\]The problem is NP-complete, but we have a lot of ideas for how to approximate it. In practice, however, Lloyd’s simple iterative algorithm is what works the best. But this algorithm has to start with some solution that it iteratively refines. Starting with a random subset of \(X\) usually works pretty well, but a slightly better and more robust choice is to run the following \(k\)-means++ algorithm:

The algorithm has \(k\) steps and in the \(i\)-th step, we first compute a distribution over \(X\) where the probability of \(x \in X\) is proportional to \(\sum_{x \in X} \text{min}_{c \in C_{i-1}} \lVert x-c\rVert^2\) Here, \(C_{i-1}\) is the set of centers sampled so far. Then, we sample the next center from that distribution (in the special case of \(i=1\), we sample from uniform distribution). After \(k\) sampling steps, we have our solution.

What’s remarkable is that this simple algorithm is a so-called approximation algorithm – its solution can only be \(O(\log k)\) worse than the optimum; and the subsequent Lloyd’s algorithm can only improve it.

Together with Christoph Grunau and others, we did some research on the variants of this algorithm.

Scikit-learn k-means works

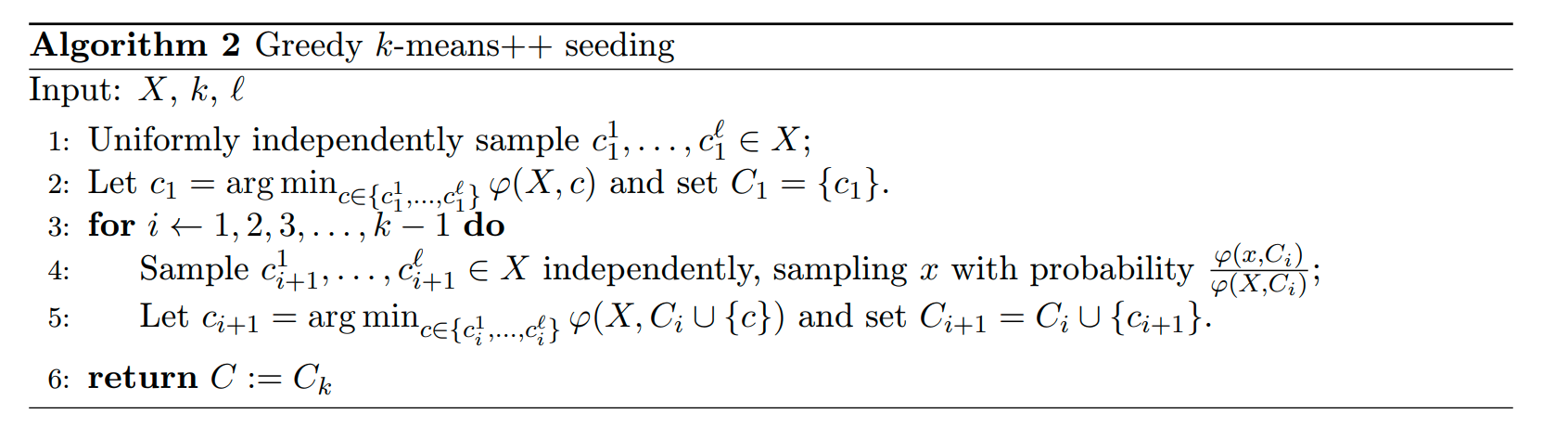

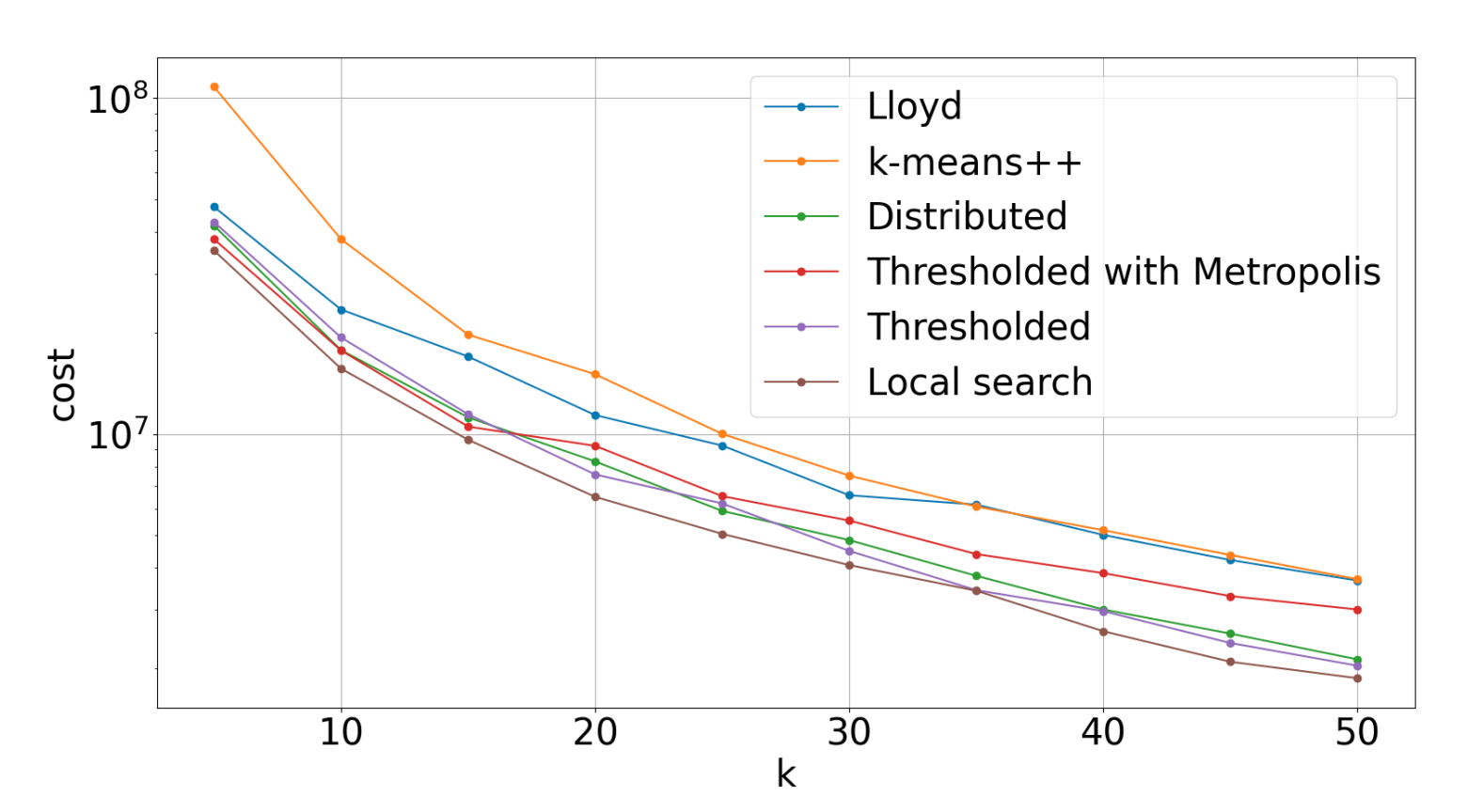

The Scikit-learn library implementation of \(k\)-means uses a variant of the \(k\)-means++ algorithm where in every step, instead of sampling just one center, it samples \(\log k\) candidates and picks the candidate \(c\) that minimizes the current cost. That is, \(c\) minimizes \(\sum_{x \in X} \text{min}_{c' \in C \cup \{c\}} \lVert x-c\rVert^2\). They use this algorithm since in the original paper suggesting \(k\)-means++, the authors pointed out that this version behaves a bit better and left open the analysis of the algorithm. Surprisingly, analyzing this algorithm turns out to be much harder than the original \(k\)-means++. In a paper with Christoph Grunau, Ahmet Alper Özüdoğru and Jakub Tětek, we showed that this algorithm is still an approximation algorithm, though with somewhat worse theoretical guarantee of \(O(\log^6 k)\) (which can’t be improved).

Adapting k-means to outliers

Here’s a variant of the \(k\)-means problem: we are additionally given a parameter \(z < n\) representing the number of outliers. We are to label \(z\) points as outliers so as to minimize the \(k\)-means cost of the remaining \(n-z\) points. In a paper with Christoph Grunau, we showed that some variants of the \(k\)-means++ algorithm generalize to this setup and checked that they work pretty well in practice.

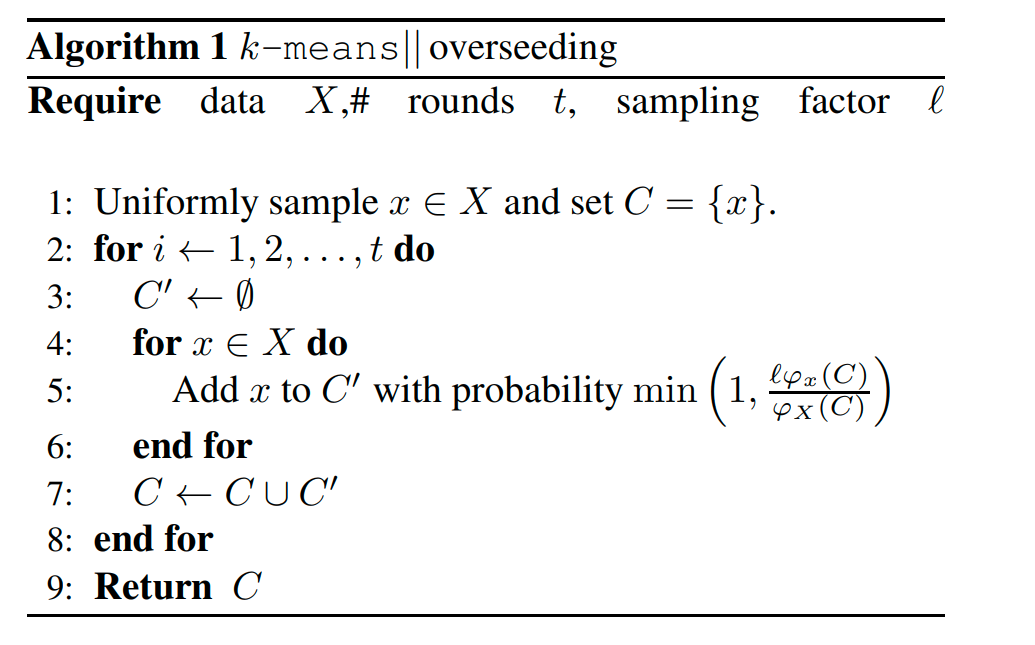

Simple analysis of k-means||

\(k\)-means|| is a parallel version of \(k\)-means++. The original paper also proves analyzes this algorithm, but the analysis is quite complicated. In this paper, I provided a very simple alternative analysis of the algorithm.